Our innate capacity to learn, to think, to create, and adapt endowed us with the evolutionary advantages necessary to become one of the most successful organisms on the planet.

In spite of mankind’s amazing potential, it is an ironic truism of modernity that our US educational system is losing massive numbers of young learners each year to boredom, stress, and disengagement, (1, 2) the same learners who can memorize 10,000 Pokémon characters and devote countless hours to leveling up on a Skinnerian game like Angry Birds(3), act up, act out, and drop out in increasing and frightening numbers. According to Sir Ken Robinson modern American Education has fallen prey to the terrible twin pillars of a collapsing 19th Century dinosaur which we know as the Industrial Revolution:

(i) Stuck in an outmoded economic theory, and

(ii) Post-colonial cultural quagmire. A mere 100 years ago, E. P. Cubberley, dean of education at Stanford (back in the day), was instrumental in drawing up the blueprint for American public education, with this infamous pronouncement

“Our schools are, in a sense, factories in which the raw products (children) are to be shaped and fashioned into products to meet the various demands of life.”(4)

Thus was birthed, the factory conveyor-belt system that purports to make education efficient and cheap, but which, in reality, has failed our young people from the very outset. (5) We know that labeling and stratifying children are a disservice to both the individual and the educational system.(6) The latest research in neuroscience and learning sciences attest to mistakes of a system that has defined our stagnant educational achievement scores since the 1950s.(7) Emergent research in neurobiology(8) and epigenetics(9) further define the incredible errors of a system that continues to fail our children by not taking into account the individual’s autonomic nervous system reactivity to social context or polygenic score that dictates an individuals propensity to learn or not. In other words, we have been straddled to our detriment with an outmoded system for more than a century—and it shows.

All children have unlimited potential. To label is to limit. Every label is a step away from limitless possibilities. Data from the online Kahn Academy confirms this. All children can earn an A. Some do it immediately, some take a little time, and others take a little more time. But we do not punish them based on the snapshot of a particular day.

The problems associated with an outmoded behaviorist teaching system is ubiquitous. Teachers, Facilitators, Salespeople, Parents, & Trainers, struggle with their work every day. And its not just in the classroom. If you’re a Trainer you fight this process every time you engage a new hire, every time you learn a skill yourself, and every time you teach your child something new. You’re not alone—everyone uses this traditional method to some degree, subconsciously and with intentionality.

It’s not your fault. You’re just using the tool we’re all familiar with. You were introduced to this method in grade school, drilled in it by high school, owned it through higher education. And by the time you entered the workforce, it had solidified into your psyche. And like everyone else, it’s likely the only approach to teaching you’ve ever known. So why would you think to use anything else?

John Medina, a developmental molecular biologist, and author, succinctly writes to the frustration of the matter. He states, “If you wanted to create an education environment that was directly opposed to what the brain was good at doing, you probably would design something like a classroom. If you wanted to create a business environment that was directly opposed to what the brain was good at doing, you probably would design something like a cubicle. And if you wanted to change things, you might have to tear down both and start over.”(10)

The most widespread and traditional model of teaching/learning is rooted in an antiquated behaviorist ideology (one that fell out of favor with learning scientists and psychologists who described a cognitive revolution in the mid-1950s). Referred to often as operant conditioning, instrumental learning, stimulus-response, or classical conditioning it harkens back to Pavlov’s salivating dog, Thorndike’s hungry cat escaping a puzzle box, and Skinner’s pigeons that could ‘read’ or ‘drop’ bombs. Indeed, it appeared to work well for animals that were half-starved and willing to work for food (reward) and/or avoid electric shocks (punishment), but it doesn’t necessarily work so effectively for well-fed children or humans who are able to use their brains and think with their free will. Behaviorism operates in a system where rewards for good behavior are intended to reinforce and increase the good behavior, while punishment for bad behavior is designed to decrease said bad behavior. This carrot and stick method does not work for people since it is premised on extrinsic motivators—the very rewards and punishments designed to instigate intrinsic motivation.

We’ve found that it works great for dogs, cats, & pigeons—at least for hungry dogs, cats, & pigeons—but it doesn’t work for people…especially people who aren’t hungry.

In preschool, depending on the teacher and the classroom environment, you were somewhat free to experiment as you learned. No one was grading you on your Lego house or your finger paintings. What’s more, you weren’t wondering whether your Lego houses were good or bad. Instead, you were simply delighted by the act of creating something out of nothing. You were more or less able to learn how to interact with other children and the world around you on your own terms, in your own way.

Once you entered kindergarten, however, things changed. You received your first grades, cleverly disguised as star stickers or smiley faces. At this young age, the education system already stratified you as a three-star, two-star, one-star, or no-star student. You could barely tie your shoes, yet you could already separate the “smart” kids from the “dumb” kids. In grade school, aptly named for the time in your life that arbitrary letters A – F dictated your self-worth, the plot thickened and your identity became absorbed by your academic score. At six years old, you could clearly see some of your classmates advancing more quickly than others.

As you moved through the grades, this structure became more and more apparent. By high school, some children and young adults received college credit, while others struggled in remedial classes. If you graduated from high school, you decided whether to continue your education or join the workforce. Your high school GPA greatly influenced that decision. Whatever route you chose, this system further stratified you.

If you went on to college, you continued as an A–F student, with your average letter grade determining whether you could advance to postgraduate education, and subsequently determining how much money you would make as an adult.

If you pursued employment, that A turned into a raise, a better office space, or prestige among your colleagues. That F often transposed into poor work reports or lateral/downward movements in the company.

What happened to the brain with limitless potential? Had it not been present in first grade and all the way up through university and then your career? Why did labeling & stratification prevent some people from achieving their true potential? Do you know people who fell by the wayside in this perverse academic and stratified journey? When it gets personal, we realize traction. When it is “my child” or “my sister or brother” who is struggling in a reward-punishment system, then we are willing to look deeper into the situation and suggest solutions that make sense from a neurobiological standpoint.

The neuroscience of learning wasn’t available a few years ago. It is now–a 100% proven pedagogic model. Innovative school districts are clamoring for professional development (PD) for Neural Education.(11) Innovative businesses are implementing Brain-centric Design with jaw-dropping results.(12) These neuroscience methods deliver information the way the brain accepts it, and how people love to learn.

If ‘Innovative’ is defined as, introducing new ideas; original and creative in thinking, and a better, scientifically-proven way to educate is available, now, shouldn’t we all move forward? Now?

If you’re lucky, you can scrape by teaching with traditional models. If you’re unlucky, they zap your audience’s desire to learn.

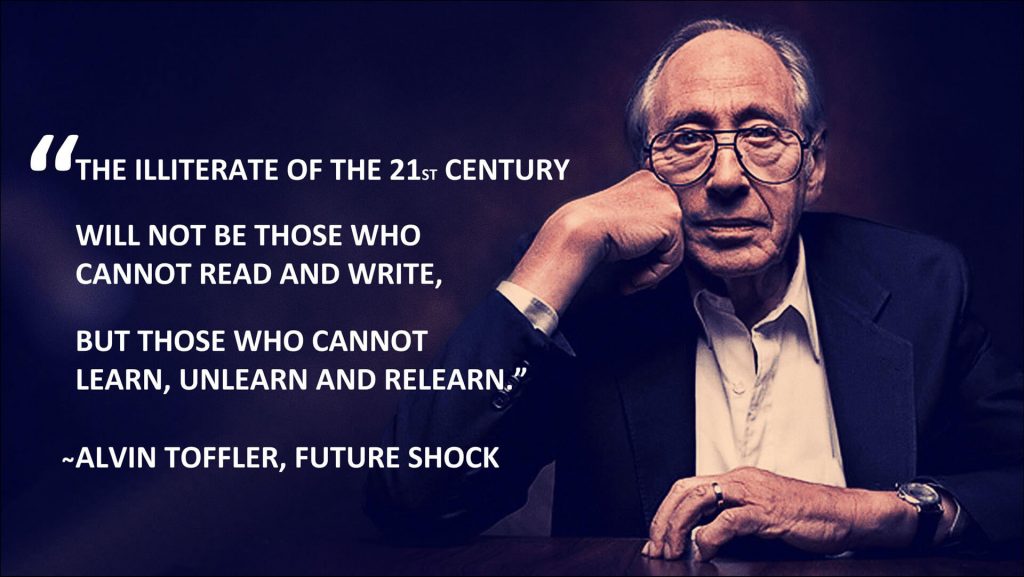

It’s time to unlearn & relearn learning.

References

1. W. Haney, G. Madaus, L. Abrams, J. Miao, I. Gruia, “The education pipeline in the United States 1970-2000,” (The National Board on Educational Testing and Public Policy, Boston, 2004).

2. University of California, California high school dropouts cost state $46.4 billion annually. UC Santa Barbara. 2007 (http://www.ia.ucsb.edu/pa/display.aspx?pkey=1643).

3. R. Stevens, T. Satwicz, L. McCarthy, in The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning, K. Salen, Ed. (The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2008), pp. 41-66.

4. E. P. Cubberley, Public school administration: a statement of the fundamental principles underlying the organization and administration of public education. (Houghton Mifflin, New York, 1916).

5. N. Chomsky, Review of B. F. Skinner, Verbal Behavior. Language 35, 26-58 (1959).

6. C. Wendelken et al., Frontoparietal structural connectivity in childhood predicts development of functional connectivity and reasoning ability: A large-scale longitudinal investigation. Journal of Neuroscience 37, 8549-8558 (2017).

7. A. J. Coulson, New NAEP scores extend dismal trend in US Education productivity. CATO at Liberty, Cato Institute. 2013.

8. W. T. Boyce, The Orchid and the Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle and How All Can Thrive. (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, New York, 2018).

9. R. Plomin, Blueprint: How DNA makes us who we are. (Random House, London, UK, 2018).

10. J. Medina, Brain Rules: 12 principles for surviving and thriving at work, home and school. (Pear Press, San Francisco, 2008).

11. T. K. O’ Mahony et al., in Edulearn 17: Neuroscience foundations – 9th Annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies. (Open Education Europe, Barcelona, Spain, 2017).

12. T. K. O’ Mahony, E. Thompson, R. Carr, in International Conference on E-Learning in the Workplace. (Teachers College, Columbia University Teachers College, New York, 2019).